Government levies levied in vain.

By Lyle Dunne

So my, my, we’re a few Billion shy,

We’d get heavy with the levy but the levy’s too high…

- or so I wrote at the start of the millennium, when healthcare funding was an issue, as it always is.

(I have heard this version was sung in Parliament House; I can confirm that it was criticised for being “as long as the original”.)

Reflecting on this now, I find the pun about levies, levees and holding back the flood has a certain resonance.

Personally, I’ve always though the Medicare Levy was the budgetary equivalent of the Emperor’s New Clothes.

In reality, all tax on income is income tax, and the top marginal tax rate is really 46.5%, not 45%, despite the tacit agreement – one might say conspiracy – to pretend that the Medicare levy is a thing apart.

It would be possible to claim it was real if you went into a Medicare office in about November, and found a sign saying “sorry, no more refunds – this year’s Medicare Levy has been exhausted. Meanwhile, take two aspirin and call us in July”.

But far from being tied to the Medicare Levy, the cost of Medicare on any definition far exceeds the levy, and always has. Thus any argument that the levy represents, even approximately, a sacrosanct pool of funding for Medicare that should not be subject to the process of negotiation in trying to balance a budget – or minimise a deficit – would be risible.

Nor can one claim that it’s a kind of de facto “user pays” system, like funding road maintenance from fuel levies. Everyone’s a user, and the ones who pay most tend to be those who use least. (Redistribution has its place, but user-pays it ain’t.)

There is, in short, no economic argument for calling a piece of income tax a “Medicare Levy”. The political benefits are that it makes Medicare look cheaper than it is (and thus more appealing), and it makes income tax rates look (slightly) lower.

Why Oppositions go along with this is less clear – perhaps inertia, or the fear that if they oppose this sham, they’ll be characterised as opposing Medicare.

Don’ pay nuttin’

Now the Gillard government is proposing to increase the levy that doesn’t pay for Medicare, by adding a component that doesn’t pay for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. It seems the increase will raise around $3.3 billion, whereas the scheme will cost around double that, in net terms.

Incidentally, the government refers to “an increase of half a percent”, because that doesn’t sound much. But what’s proposed is an increase in the rate of the so-called Medicare Levy of a third – 1.5% to 2%. To pay for the actual cost of the disability scheme as estimated, it would have to be around two-thirds. How long would it take before the cost of the scheme exceeded what governments pretend Medicare costs?

Of course, the government says costs will not grow, but be offset over time by the benefits of early intervention: reduced costs of support via disability pensions, and increased revenue from former pensioners (or people who would otherwise be pensioners) becoming taxpayers.

Gee, I wish I believed them.

The arguments are of such a complex and frankly speculative nature that it’s really not possible to address them in detail. However my gut feeling is that over time, expectations on the part of beneficiaries, family members and practitioners will grow, driving and being driven by growth in the numbers of beneficiaries and practitioners, since assessment of needs is subjective, and is inevitably done in the light of what’s likely to be available, and what’s seen as reasonable. I expect this will produce a blow-out in costs which will dwarf any savings on the tax-pension side.

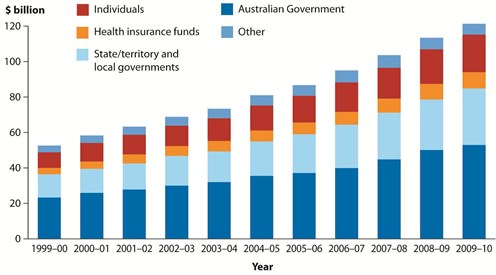

I’m not a Malthusian, but it looks to me like a case of geometric growth drivers vs arithmetic savings. We can’t be certain, but a glance at the health budget in recent decades suggests a likely cost trajectory.

Australia Health Spending (Based on AIHW 2011a. Health expenditure Australia 2009-10. Health and welfare expenditure series no. 46. Cat. no. HWE 55. Canberra.)

Of course, that’s not to say we shouldn’t implement the scheme. There’s a strong argument that we should be putting more of our steadily-growing wealth into providing for the needs of the most disadvantaged members of our society. However we should go into it with our eyes open, and not pretend it’s cheap or free when in fact it’s going to be very expensive.

If we had a rational debate about the costs and benefits, we might still want the scheme, but we might think about the timing – maybe black-hole-deficit territory isn’t the ideal time to start – and perhaps the scale. It’s been presented as an all-or-nothing deal, but in theory there’s no reason an expansion in services for the disabled couldn’t be phased in, nor that it has to be at the scale suggested.

Abbott, however, seems to have made the rational calculation that, given the polls, he should just Keep Calm and Carry On, and avoid risky policy debates.

Levy? What levy?

Of course, one reason he isn’t pointing out the absurdity of the levy sham is that the Opposition has its own controversial levy plan: a 1.5% tax on big business to fund paid parental leave.

The dilemma with paid parental leave was always that a fixed benefit like Labor’s scheme provided would only appeal to low-paid workers, whereas a scheme that related to actual salary would be regressive, paying more to higher-income earners.

The reason for pinning this on “big business” is presumably to offset the political downside of this reverse-Robin-Hood effect. At the same time, the discussion of a “modest” reduction in company tax (previously quantified, coincidentally, at 1.5%) gives rise to some pea-and-thimble concerns.

The Liberals are currently trying to put out a few spot fires on this one, with the ABC quoting disgruntled federal Liberal backbencher Alex Hawke ‘calling it an “albatross” that must be “scrapped”’.

(I’m not familiar with the process of Albatross-scrapping, but I hope it’s humane.)

Hawke’s IPA Article on the subject, which I note is free of references to seabirds, makes a persuasive case that this is an impost that Australian business cannot afford at this time if it is to remain competitive.

Nonetheless if we are not to go the way of Japan, and the countries of southern Europe, we need to avoid a shrinking and ageing population. And it seems, with high female workforce participation here to stay, that appealing maternity-leave provisions are a necessary part of maintaining the birthrate.

Essentially, this is a problem of redistributing resources over one’s lifetime: even high income earners face high costs during their child-rearing years, but it seems unreasonable for those on lower incomes to subsidise them.

The obvious solution seems to me to be a system where the cost of parental leave – or perhaps the difference between the current basic-wage rate, and actual salary — is funded by the beneficiary, from later earnings.

This “loan” could be interest-free, or at a subsidised interest rate. Repayment could be deferred until income – I’d suggest household rather than individual income – reached a level where they could afford it. Of course, some households might never reach that threshold, but they would be a minority, and probably those who’d done more than their share of child-rearing anyway.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because I’ve lifted it shamelessly from the HECS model for funding tertiary studies.

It wouldn’t be free, but it would be more of a seagull than an albatross.