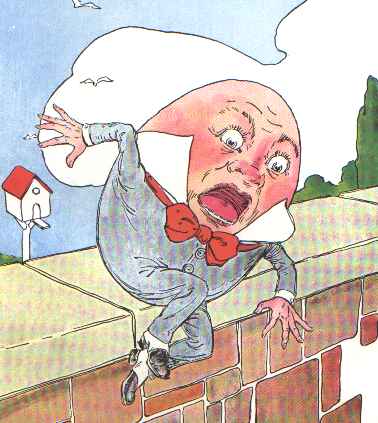

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

- Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

By Lyle Dunne

As I write, the ACT has just made history by becoming the first jurisdiction in Australia to purport to allow same-sex marriage.

I say “purport”, not to indicate that I disapprove (although I do), but to acknowledge the fact that the Commonwealth has made it clear that it will challenge the validity of this law in the High Court. If this challenge succeeds, of course, the Court will confirm that the ACT government lacked this power, so it will not in fact have legitimised same-sex marriages.

In the lead-up to this debate, the ACT government brought in some last-minute amendments to the Bill, including a change of title to increase the likelihood of its surviving such a challenge by including an explicit reference to “same-sex marriage”.

I’ve been surprised, throughout the broader debate, by how little discussion there has been about what we mean by “marriage”.

The issue here is not simply that constitutional safeguards are worth very little if their terms can be redefined in an unrestricted way by the legislatures they regulate — although that issue should make you at least a little nervous. There are some specific semantic concerns here – and by “semantic” I don’t mean trivial.

Semantic not trivial

Two arguments are being conducted simultaneously: whether same-sex marriages exist, or should exist; and whether state and territory governments should have control over them. Acting together, they sometimes take people to strange places.

One might suppose that “gay marriages” either were marriages, or were not; if they were, they would fall under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth by virtue of its marriage power; if they were not marriages, the ACT government could not enact laws saying they were. Either way, there would not seem to be a role for the ACT government.

But such an analysis reckons without the semantic skills of the HumptyDumptians in the ACT Government.

The paradox here is that, in order to claim a right to control same-sex marriages, the ACT government has to accept a definition of marriage that excludes them.

It seems the ACT government’s position is broadly thus:

- We recognize that the Commonwealth has a Constitutional right to legislate in relation to “marriage”, by which they mean a union between a man and a woman;

- We accept that definition in relation to Commonwealth law;

- We however claim the right to legislate in relation to other types of unions, including the right to call them “marriages”;

- Having deemed these relationships “marriages” in the broader, ACT-specific sense, we expect them to be treated as marriages in the narrower, Commonwealth-specific sense (including, presumably, under Commonwealth social security and tax law) — even though, as we’ve just acknowledged, they are not marriages in that sense.

But just because it’s absurd doesn’t mean it won’t succeed. One should not rule out the possibility that the Humpty-Dumptian constitutional interpretation will triumph, and marriage be agreed to have two different, simultaneous interpretations: sometimes the Vibe of the Thing can be a little discordant.

” … just because it’s absurd doesn’t mean it won’t succeed. One should not rule out the possibility that the Humpty-Dumptian constitutional interpretation will triumph … ”

Perhaps I’m being unfair to Mr Dumpty: he claimed the right to alter the sense of words at will, but not to give the same word two different meanings at once, or treat statements as true when he’d just affirmed the opposite.

But there is a further dimension to the meaning of “marriage”: when people say gay marriage should be allowed, what do they understand the nature of marriage to be — quite apart from the question of who’s entitled to it?

Do they mean same-sex couples should be able to propose on bended knee, send out wedding invitations, receive wedding presents, be pronounced wife and wife, have a cake with two figures in top hats, wear matching white dresses, have “just married” painted across the back of the car?

From the public commentary, it seems many do mean that – but of course, there’s nothing to stop them doing any of those things now.

Of course, celebrants can refuse to officiate, and perhaps some imagine that this might change under ACT-style legislation. But in fact the ACT law does not grant a right to demand marriage from a particular celebrant, and it’s not hard to see why. Most religious celebrants would not marry a couple who were not members of their denomination. A Catholic priest would not marry a heterosexual couple if one had a living spouse or “ex”, or a defect of intent in relation to fidelity or children. Changing this would be a radical innovation indeed, with implications far beyond the issue of same-sex couples.

More than weddings

So if there’s any rationality to the same-sex-marriage position, marriage must be about more than weddings: it must be something to do with legal rather than social status.

But the relation between the law and marriage is not a straightforward one.

I suspect that most gay-marriage advocates assume that marriage is a creature of the law, and like Humpty Dumpty we can make it mean what we want. Such a position is of course completely ahistorical: marriage existed before the law, and the law, while regulating some aspects of marriage, does not claim to create marriages.

Nor does the Catholic Church, for example, which also sees its role as witnessing the act of a couple marrying each other. It sets down conditions for sacramental marriages among believers, but recognises the legitimacy of other marriages.

Most jurists would probably say that the role of the state in relation to marriage arose from the need to safeguard the interests of dependants: the state had to be able to determine, at least after the fact, who was married, in order to resolve questions of inheritance, and property rights in the case of separation or divorce. But identifying marriage is not the same as creating it.

For most of us, the idea of marriage, with its rights and obligations, seems to belong in the same category as human rights, free will, filial obligations and the like: concepts we feel have an independent existence, in a reality outside the material world, but are nonetheless real and necessary. I think this remains true whether or not we can accommodate these concepts within a complete philosophical system.

Others, of course, will regard all such concepts as man-made constructs. To them I can only say that it seems inconsistent to mount an argument proceeding from equality or universal human rights, if these are made up too.

There seems to be little prospect of agreement about marriage law between people who regard marriage as having a reality independent of, and pre-dating, both church and state, and those who see it as something like a limited-liability company or a coöperative society.

I’m also aware of the futility of trying to approach in conceptual terms an argument that’s being conducted in the popular press at the level of “I’ll have what she’s having”.

Still less is there any prospect of a rational discussion with those whose interest in this issue is not really about marriage at all – who want to argue not from equal rights to same-sex marriage, but vice versa.

But I like to think that readers of this blog will be grown-ups, and capable of rational thought.

* Lyle Dunne is married to the Speaker of the ACT Legislative Assembly, Vicki Dunne MLA.