Régime change and popular elections in the Islamic world give rise only to new cycles of repression, not to new democracies.

By Gary Scarrabelotti

On June 26, US President Barack Obama called on Congress to vote $US500 million to support selected elements of the anti-Assad forces in Syria.

$US500 million in military terms is not a lot. It will buy only a modest package of military kit and training. By itself, it won’t turn the tide of battle against Assad, all the more so because the money will be allocated, if it is voted, to the Free Syrian Army (FSA), the least significant and effective force in the field against the dictator.

So, why is the USA dabbling in Syria when anything that enhances the capability of the Sunni rebels to hit Assad harder empowers, indirectly, the very Islamic radicals that the USA professes to oppose?

Every tank destroyed by the FSA with a US supplied missile, is one tank less that Assad can deploy against the Al Qaeda directed Jabhat Al-Nusra (JN) or the Al Qaeda break-away, and many times renamed, Islamic State (IS). In other words, the more effective the FSA bit players become, the more powerful, relatively speaking, the forces of the radical Islamists become.

Or, to put it in another way, the more effective the FSA is, the less capable of defeating JN and IS will Assad be: for it is an unpalatable truth that — short of a US invasion which is not going to happen — only the Assad government, with Russian backing, has the military potential to defeat the Islamic revolutionaries.

Those who advocate arming “moderate” Syrian rebels would respond by claiming that the FSA is weak largely because the West, and the USA in particular, has dilly-dallied over throwing its weight behind the FSA. It would have been, so the rejoinder goes, a much more formidable force, if only help had arrived earlier, and the power of the radicals would have been weakened proportionately.

Sounds plausible. But it doesn’t stack up when scrutinised under the harsh light of recent experience. For the Moslem world today is not undergoing a renaissance of moderation, or of tolerance, but a radical rediscovery of Islam’s alluring simplicity of fundamentals and violent primitivism. Given this reality, régime change and popular elections in the Islamic world give rise only to new oppressors no better than those they replaced. In this environment, liberal democracies do not take root and “moderates” are the losers.

Case: Iraq

The USA and its allies overthrew Saddam Hussein in 2003 and brought democracy to Iraq in 2005-06. Result? They (we) replaced a dictatorship and a Sunni Arab supremacy (representing one in five Iraqis) with a dysfunctional parliament, divided without compromise along sectarian and ethnic lines, and a guaranteed Shi’ite ascendancy (representing three in five Iraqis).

Well, that’s democracy for you: majority rules; but, in this case, it rules in an illiberal, winner-takes-all style for which the children of Mohammed have a genius. The now two-term Shi’ite government of Nouri Al-Maliki has pursued a policy of systematically excluding Sunnis from a place in the new Iraq and, to make it stick, has provided itself with a reserve army of Shi’ite militias whose function is to keep Sunnis down if and when they get uppity.

Not surprisingly, the Sunnis have revolted: including many from the “Awakening” movement, who allied themselves with the Americans in 2007, and who are now in bed with their old (Sunni) Al-Qaeda enemies and new (Sunni) Islamic State friends to bring down the Shi’ite government or, failing that, to cut it down to size.

It is an unpalatable truth that only the Assad government, with Russian backing, has the military potential to defeat Syria’s Islamic revolutionaries.

Case: Egypt

After a solid dose of “Arab Spring”, backed by goggle-eyed American enthusiasm, Egyptian strongman, Hosni Mubarak, surrendered the presidency in February 2011.

On November 30, 2011, an election was held in which radical Islamic parties were swept into power. The political arm of the Moslem Brotherhood, the Freedom and Justice Party, notched up 36 per cent of the vote. The even more radical Salafist “Al Nour” Party won 24 per cent. That’s 60 per cent of the vote that went to the advocates of jihad, shar’ia law, the jizya submission-tax on Christians and the most frightful anti-semitism.

The electoral triumph of real Islam led to a protracted and complex struggle between the Islamist parliament, the army and the streets – these, on one day, were awash with supporters of the Brotherhood and the Salafists and, on another, with those who feared them. There were attempted coups and counter-coups. One day the army decreed dissolution of parliament (June 2012); on another the Brotherhood president, Mohammed Morsi, granted himself supreme power (November 2012); and, finally, Morsi overreached. He appointed a clutch of Islamic radicals as governors to 13 of the country’s 27 provinces (June 2013) and the army, headed by Defence Minister Abdel Fatah Al-Sisi, overthrew him on July 3, 2013. A bloodbath followed a month later when the army attacked the Brotherhood’s protest camps on Cairo’s streets. Allegedly, 2,200 of the Brothers died in a single night’s work.

The Puzzle

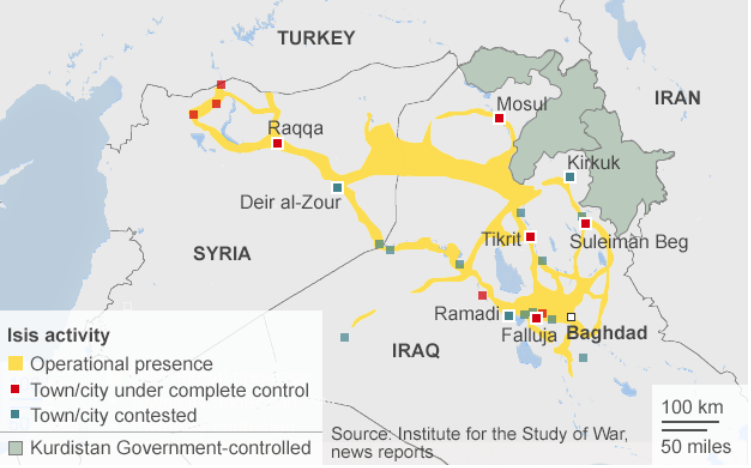

Régime change and democratisation in both Iraq and Egypt have not been conspicuous for their success. Why, then, is the USA continuing to lend its support to overthrowing Assad, especially now, when the Sunni uprising there has turned the country into a mecca for foreign jihadists — a second Afghanistan — and provided the conditions for the formation of a force more radical even than Al-Qaeda which has burst out of eastern Syria to capture western Iraq?

Now, let’s try to understand this. In Egypt the United States applauded the downfall of Mubarak and later acquiesced in the destruction of the Sunni Brotherhood by another military dictator. In Syria the US supports a Sunni uprising against a dictator. But in Iraq the Americans are trying to find a way to defeat a Sunni invasion and local uprising – and, to do this, the US will have to ally itself with Iran and Iraqi Shi’ite militiamen both of whom have stood at Assad’s side in Syria.

Agreed, the world is a complex place. I get the impression, nevertheless, of a deep, and very dangerous, confusion among American policy makers about what role America should play the Middle East. Perhaps the time has come for the apostle of world democratic revolution, to pause and recollect itself — for its own sake as well as for our own.

*Gary Scarrabelotti is the Director of a Canberra-based consulting business Aequum: Political & Business Strategies.This article is an edited version of one originally published on the Henry Thornton blog.